Trouble in paradise: Indian islands face ‘brazen’ new laws and Covid crisis

Authoritarian’ rules upset sleepy Lakshadweep’s Muslim majority while Covid cases soar from zero to 10% of population.

According to local people, the problems for Lakshadweep, an archipelago of paradise islands in southern India, began the day the new government-appointed administrator, Praful Khoda Patel, landed on a charter flight.

The Lakshadweep islands, an Indian union territory off the coast of Kerala, have a population of just 64,000 and are renowned for their crystal-blue waters, white sands and relatively untouched way of life. They had, up to that point, also remained completely unaffected by the pandemic, due to strict controls on movement and enforced quarantine.

That day, 2 December 2020, India’s Covid-19 cases had passed 9.4 million but there was not a single incidence reported across Lakshadweep’s 36 islands.

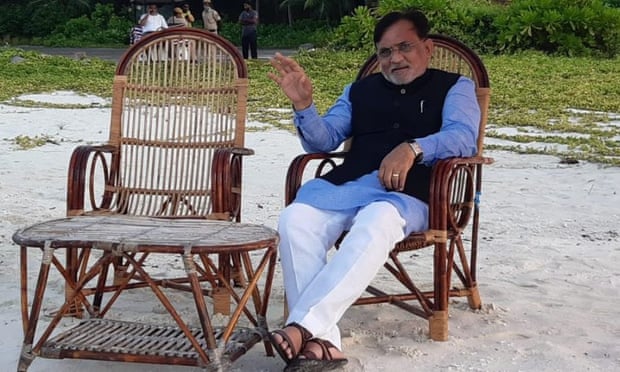

Yet much to the anger of residents, Patel, a leader in the ruling Bharatiya Janata party (BJP) who had been appointed to run Lakshadweep by his long-term ally, prime minister Narendra Modi, decided to publicly ignore the quarantine rules imposed on everyone else.

Tensions rose further when, while on the way to his official residence, Patel saw a banner imprinted with a slogan against India’s controversial new citizenship law, which has been accused of discriminating against Muslims. He ordered it to be removed and three people on whose land the sign was placed were arrested and released on bail.

Then, without consultation and despite staunch opposition, he introduced a slew of new measures and draft laws that the people of Lakshadweep, 96% Muslim, saw as an attack on their identity, religion, culture and land, and a devastating threat to their way of life.

Mandatory Covid quarantine for all arrivals to the islands was also scrapped. Lakshadweep has gone from zero coronavirus cases to being one of the worst affected areas of the country, with more than 10% of the population estimated to have been infected.

As the extent of Patel’s measures – described as “brazen”, “authoritarian” and an imposition of the BJP’s Hindu nationalist agenda on one of India’s only majority-Muslim regions – has become widely known, some of India’s most prominent politicians have voiced robust opposition.

Dozens of MPs have written to the central government and a campaign to “Save Lakshadweep” has gained traction across India. On Monday, the state assembly of Kerala, where Patel’s measures have been met with outcry, passed a unanimous resolution for the administrator to be recalled from his post.

Priyanka Gandhi, a prominent figure in the opposition Congress party, has been a particularly vocal critic. “The people of Lakshadweep deeply understand and honour the rich natural and cultural heritage of the islands they inhabit,” she tweeted. “They have always protected and nurtured it. The BJP government and its administration have no business to destroy this heritage, to harass the people of Lakshadweep or to impose arbitrary restrictions and rules on them.”

Shashi Tharoor, a senior opposition politician, added: “One could be forgiven for reading these laws as legislation for a war-torn region facing significant civilian strife, rather than laws meant for an idyllic archipelago filled with abundant natural beauty and peace-loving fellow citizens of India.”

The most divisive laws proposed by Patel include a ban on eating beef, under the guise of animal conservation; removing a four-decade ban on the consumption of alcohol and allowing liquor stores to open; banning people from running in village elections if they have more than two children; and a proposed regulation which empowers the administration to acquire land on the islands, irrespective of its ownership, for “development” purposes.

In addition, all dairy farms were closed and a businessman from Patel’s home state of Gujarat was allowed to come in and franchise milk production and sales on the islands.

Most controversially, Patel has also proposed the Prevention of Anti-Social Activities Act, or “goonda act” as it is locally known, a new law that gives police powers to jail suspects without trial, and without full evidence, for up to a year.

“People are scared by these absurd laws,” says Hassan Bodumukka, chief councillor and panchayat president on the islands. “We are Muslims and have been eating beef traditionally. Banning it is an attack on our religious identity. More than that, policies are being made to dispossess us from our land and this is all happening in the guise of development.”

No one is against development, Bodumukka says, “but it cannot be done at the cost of the environment, people, their identity and faith”.

The islands have always strictly protected themselves from the often corrosive impacts of tourism and development. Though hotels exist, they are mostly small and government-run. Special permission is required for tourists to visit the islands. Fishing in the surrounding tuna-rich waters is the islanders’ main livelihood.

Lakshadweep has flourished under these protected conditions; per capita income is higher than the Indian average, the literacy rate is 92%, much higher than India’s average of 74%, and crime is negligible.

But Patel and the Modi government appear to have their sights set on developing Lakshadweep into a major tourist destination, including paving new roads and creating a designated “smart city” in the capital, Kavaratti. For islanders and former administrators, these plans signal the beginning of the end of Lakshadweep as they know it.

“Tourism development in Lakshadweep must be people-centric, not investor-centric,” says Wajahat Habibullah, former administrator of the region. “The idea is to preserve the ecology because these are very fragile ecological entities. The Maldives [which is adjacent] is already facing this problem of extinction because the reefs have been compromised, which, fortunately, has not happened in Lakshadweep to that extent. We need to preserve those reefs.”

Already, sheds along the seafront belonging to local fishers have been demolished and trees have been cut down to make way for new roads. Rumours are rife that the islands will be opened up for development by large hoteliers and corporations, leaving people fearful that their land will be grabbed from them.

“We fear losing our land,” says Mohammed Faizal, the islands’ only MP, who is from the Nationalist Congress party. “All the people living in Lakshadweep are scheduled tribes and their land is protected under the constitution. No one can come here and take our land.”

Faizal adds that the government is trying to make land grabs legal under the guise of development.

Patel served as home minister of Gujarat from 2010 until 2012. He was then appointed administrator of Daman and Diu followed by Dadra and Nagar Haveli, now merged into one union territory which includes Diu island off the coast of Gujarat. Patel was accused of imposing laws which infringed local customs by bringing major development and a tourism push to the island, which saw heritage buildings demolished to build roads.

Many fear the same, or worse, for Lakshadweep. Abdul Salam, general secretary of the Congress party on the islands, says people “have been living here for generations and most of us are self-sufficient. We don’t want corporations to come here with the aim to dispossess us.”

Patel did not directly respond to requests for comment, but the BJP has denied all the allegations, saying Patel’s new measures were “aimed at the overall development of the island” and that his administration in Lakshadweep had fallen prey to a politically motivated “misinformation campaign”.

This week, Faizal said he had been given assurances by central government that nothing would be introduced without the consent of the islanders.

Most of the new laws are awaiting final approval from cabinet. But some decisions have already affected hundreds of people and elected bodies have been stripped of key powers.

While there have been protests on the island, Patel’s “goonda act” has left people scared to voice their opposition to the regime for fear they will be locked up without trial.

Twenty-one people, including elected representatives who resisted the change in quarantine policy, have had police cases filed against them and many others have been arrested.

“We have seen what is being done with the Muslims in India,” says Mohammad Saalim, a college student from Lakshadweep. “From Kashmir to Delhi, and other places, laws are being made by the Modi regime to make Muslims second-class citizens, and the same is happening with us now.”