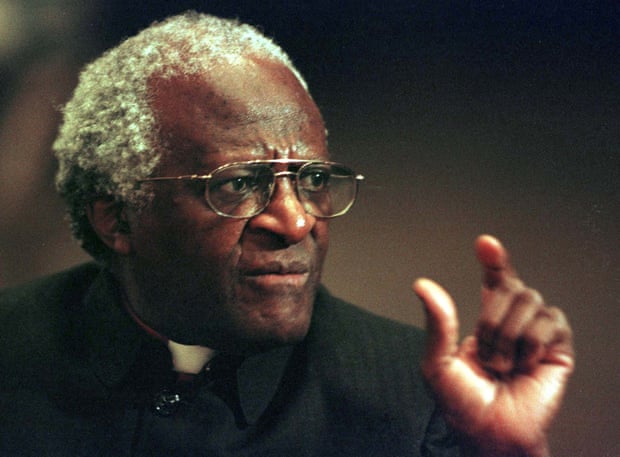

Anti-apartheid hero Archbishop Desmond Tutu dies aged 90

The Nobel laureate, often described as South Africa’s moral conscience, died in Cape Town on Boxing Day

Desmond Tutu, the South African cleric and social activist who was a giant of the struggle against apartheid, has died aged 90, prompting tributes from religious leaders, politicians and activists from around the world.

Tutu, described by observers at home and abroad as the moral conscience of the nation, died in Cape Town on Boxing Day, weeks after the death of FW de Klerk, the country’s last white president.

“The passing of archbishop emeritus Desmond Tutu is another chapter of bereavement in our nation’s farewell to a generation of outstanding South Africans who have bequeathed us a liberated South Africa,” said President Cyril Ramaphosa. “From the pavements of resistance in South Africa to the pulpits of the world’s great cathedrals and places of worship, and the prestigious setting of the Nobel peace prize ceremony, the Arch distinguished himself as a non-sectarian, inclusive champion of universal human rights.”

Tutu was diagnosed with prostate cancer in the late 1990s and in recent years was hospitalised on several occasions because of infections associated with his treatment. He died peacefully in the early hours of Sunday morning, according to his relatives.

The Queen said Tutu “tirelessly championed human rights in South Africa and across the world”, and the archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, described him as a “prophet and priest, a man of words and action – one who embodied the hope and joy that were the foundations of his life”. The former US president Barack Obama said Tutu was as “a mentor, a friend and a moral compass for me and so many others”.

The South African cricket team wore black armbands in his honour on the first day of the first Test against India in South Africa.

A seven-day mourning period is planned in Cape Town before Tutu’s burial, including a two-day lying in state, an ecumenical service and an Anglican requiem mass at St George’s Cathedral in Cape Town, according to church officials. Cape Town’s Table Mountain will be lit in purple, the colour of the robes Tutu wore as archbishop.

Tutu was born in Klerksdorp, a farming town 100 miles (160km) south-west of Johannesburg. The sickly son of a headteacher and a domestic servant, he trained first as a teacher before becoming an Anglican priest.

As a cleric, he travelled widely, gaining an MA in theology from King’s College London. Though he only emerged as a key figure in the liberation struggle in the mid-1970s, he was to have a huge impact, becoming a household name across the globe.

Excitable, emotional, charismatic and highly articulate, Tutu won the Nobel peace prize in 1984. A vocal supporter of sanctions against South Africa, he was detested by supporters of the apartheid regime, who saw him as an agitator and traitor. Tutu was however protected not just by his wit and combative spirit, but by his immense popularity and respect. In 1986 he was appointed archbishop of Cape Town, the effective head of the Anglican church in his homeland.

Tutu always kept his distance from the African National Congress (ANC), the party that spearheaded the liberation movement and has now been in power in South Africa for more than 20 years. He refused to back its armed struggle and support unconditionally leaders such as Nelson Mandela.

However, Tutu shared Mandela’s vision of a multiracial society in which all communities lived together without rancour or discrimination and is credited with coining the phrase “rainbow nation” to describe this vision.

After the nation’s first free election in 1994, Mandela, who had become the president of a free South Africa, asked Tutu to become chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), the controversial and emotional hearings into apartheid-era human rights abuses.

The TRC was described as the “climax of Tutu’s career” and lauded across the world as a pioneering effort to heal deep historical wounds.

However, Tutu found the experience deeply traumatic. He was saddened and perplexed by the ferocious criticism from the white right wing, some mainstream liberals and the ANC. The terrible testimony that he listened to day after day brought deep emotional stress too, with TV viewers watching as the tough, witty cleric put his head in his hands and wept.

In the late 1990s, Tutu, suffering from prostate cancer, began to spend more time with his wife of 60 years, four children, and numerous grandchildren. He continued to criticise the ANC and was initially excluded from the state funeral of Nelson Mandela in 2013. His absence provoked a public outcry. Tutu later said he had been “very hurt”.

Despite his illness, Tutu remained interested in world affairs and determined to use his enormous moral prestige to make a difference. In 2015, he launched a petition urging global leaders to create a world run on renewable energies within 35 years, which was backed by more than 300,000 people globally. It described climate change as “one of the greatest moral challenges of our time”.

He also spoke out against homophobic legislation in Uganda and argued in favour of assisted dying.

Mandela, who lived near Tutu’s home in Soweto and also won the Nobel prize, once described his close friend as “sometimes strident, often tender, never afraid, seldom without humour”. “Desmond Tutu’s voice will always be the voice of the voiceless,” he added.

Among those paying respects at Cape Town’s St George’s Cathedral on Sunday was Miriam Mokwadi, a 67-year-old retired nurse, who said the Nobel laureate “was a hero to us, he fought for us”.

“We are liberated due to him. If it was not for him, probably we would have been lost as a country. He was just good,” Mokwadi told Agence France-Presse, clutching the hand of her granddaughter.

Friends remembered Tutu as a man of deep faith whose charm, warmth and intelligence few could resist, and who was happiest when active on behalf of others.

“I love to be loved,” he told the BBC’s Sue Lawley when appearing on Desert Island Discs in 1994.